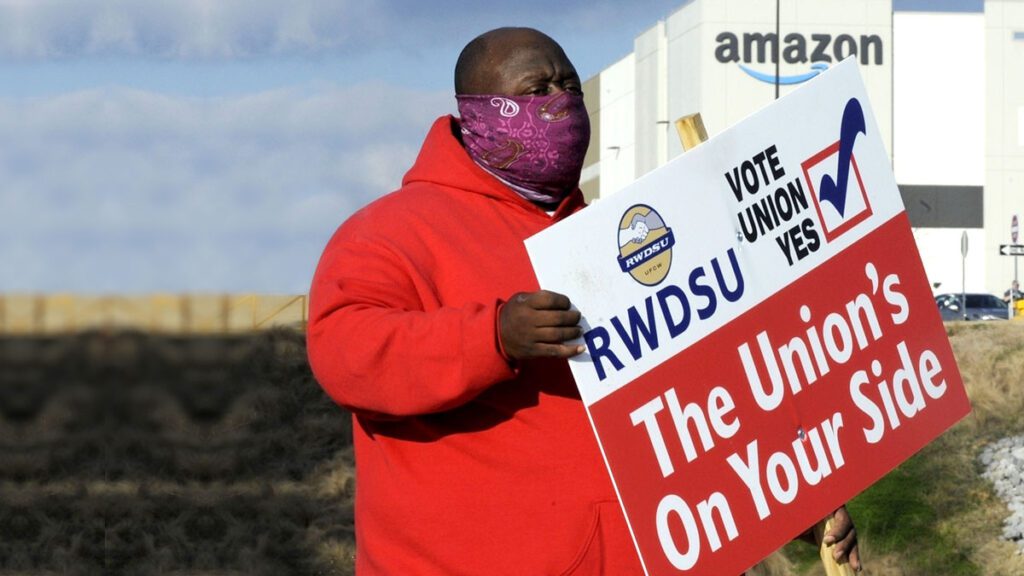

Nearly 6,000 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama, are deciding whether they want to form a union, the biggest labor push in the online shopping giant’s history.

The stakes are high for Amazon. The organizing in Bessemer could set off a chain reaction across its operations nationwide, with more workers rising up and demanding better working conditions. Meanwhile, labor advocates hope what’s happening in Bessemer could inspire workers beyond Amazon to form a union.

But organizers face an uphill battle. Amazon, the second-largest private employer in the country, has a history of crushing unionizing efforts at its warehouses and its Whole Foods grocery stores.

Workers in Bessemer have until Monday to cast their votes. A majority of voters must vote “yes” in order to form a union.

Here’s more on the unionization efforts:

WHAT DO ORGANIZERS WANT?

Besides higher pay, they want Amazon to give warehouse workers more break time and to be treated with respect. Many complain about their back-breaking 10-hour workdays with only two 30-minute breaks. Workers are on their feet for most of that time, packing boxes, shelving products or unpacking goods that arrive in trucks.

One worker in Bessemer who recently testified at a Senate hearing described the work as “grueling” and said workers are tracked throughout the day and could be punished or fired for taking more break time.

In job postings, Amazon describes the warehouse jobs as a “fast-paced, physical position that gets you up and moving.”

WHAT’S AMAZON’S RESPONSE?

Amazon argues the warehouse created thousands of jobs with an average pay of $15.30 per hour — more than twice the minimum wage in Alabama. Workers also get benefits including health care, vision and dental insurance without paying union dues, the company said.

Amazon has been pressing workers to vote against the union. At the Senate hearing, one worker testified that the company hung anti-union signs throughout the Bessemer warehouse, including inside bathroom stalls, and also holds mandatory meetings for workers about why the union is a bad idea. It has created a website for employees that tells them they’ll have to pay $500 in union dues a month, taking away money that could go to dinners and school supplies.

However, Alabama is a “right-to-work” state, which allows workers in unionized shops to opt out of paying union dues even as they retain the benefits and job protection negotiated by the union.

WHY IS THIS HAPPENING NOW?

Labor historians point to two reasons, the first being the pandemic: Workers feel betrayed by employers that didn’t do enough to protect them from the virus. At the start of the pandemic, for example, Amazon workers held walkouts because they said they weren’t given protective gear or told when coworkers tested positive for the virus.

The second is the Black Lives Matter movement, which has inspired people to demand to be treated with respect and dignity. Most of the workers in the Bessemer warehouse are Black, according to organizers.

The last time Amazon workers tried to unionize was in 2014 at a warehouse in Delaware. But the majority of the 30 employees there ultimately voted against it.

WHAT HAPPENS IF WORKERS AGREE TO UNIONIZE?

Amazon would need to start negotiating a contract with the New York-based Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, which is leading the organizing efforts for Bessemer warehouse employees and represents 100,000 workers at poultry plants; cereal and soda bottling facilities; and retailers such as Macy’s and H&M.

But Amazon could stall contract negotiations and both sides could launch legal actions, delaying the process.

A union win in Bessemer does not mean a union win at the more than 230 other Amazon warehouses spread across the country. Each warehouse that wants to unionize would have to go through a similar process.

But if organizers succeed in Bessemer, it could inspire workers in other parts of Amazon to try as well. Even if organizers lose, the fact that the union push got this far in a right-to-work state could encourage workers in states with more lenient labor laws to mount a similar effort.

Amazon employed nearly 1.3 million workers worldwide at the end of last year, making it the second-largest private employer behind retailer Walmart. Amazon hired 500,000 people last year alone to keep up with a surge of online orders during the pandemic.

WHAT DOES THE VOTING PROCESS LOOK LIKE?

Mail-in voting started in early February. Ballots must be received by the end of the day Monday. The National Labor Relations Board starts counting votes the next day.

It could take days or longer to tally all the votes, depending on how many are received. Amazon or the union could contest votes for various reasons, which could prolong the count.

NEW YORK (AP) — By JOSEPH PISANI