Tech experts in China who find a weakness in computer security would be required to tell the government and couldn’t sell that knowledge under rules further tightening the Communist Party’s control over information.

The rules would ban private sector experts who find “zero day,” or previously unknown security weaknesses, and sell the information to police, spy agencies or companies. Such vulnerabilities have been a feature of major hacking attacks including one this month blamed on a Russian-linked group that infected thousands of companies in at least 17 countries.

Beijing is increasingly sensitive about control over information about its people and economy. Companies are barred from storing data about Chinese customers outside China. Companies including ride-hailing service Didi Global Inc., which recently made its U.S. stock market debut, have been publicly warned to tighten data security.

Under the new rules, anyone in China who finds a vulnerability must tell the government, which will decide what repairs to make. No information can be given to “overseas organizations or individuals” other than the product’s manufacturer.

No one may “collect, sell or publish information on network product security vulnerabilities,” say the rules issued by the Cyberspace Administration of China and the police and industry ministries. They take effect Sept. 1.

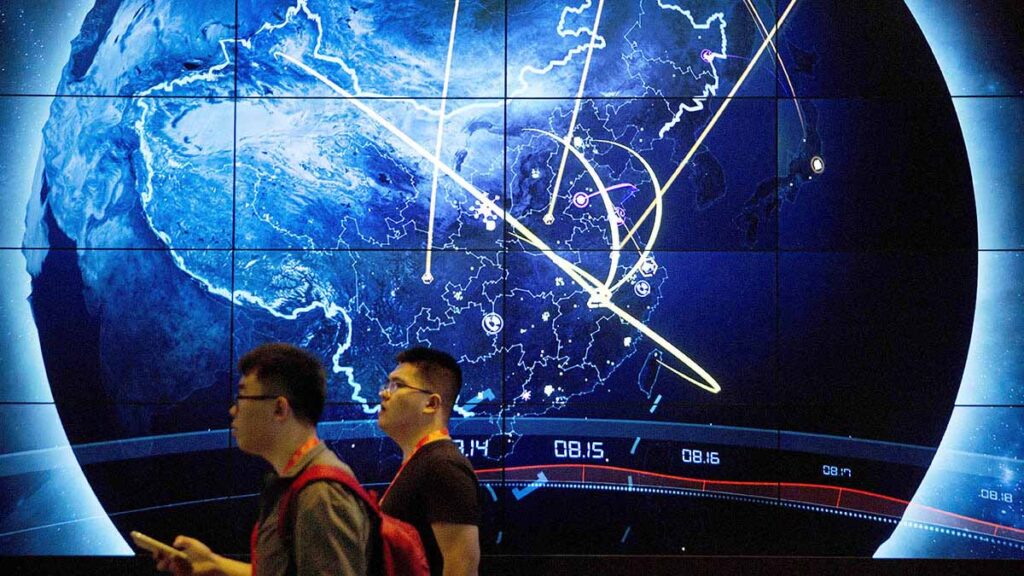

The ruling party’s military wing, the People’s Liberation Army, is a leader along with the United States and Russia in cyber warfare technology. PLA officers have been charged by U.S. prosecutors with hacking American companies to steal technology and trade secrets.

Consultants that find “zero day” weaknesses say their work is legitimate because they serve police or intelligence agencies. Some have been accused of aiding governments accused of human rights abuses or groups that spy on activists.

There is no indication such private sector researchers work in China, but the decision to ban the field suggests Beijing sees it as a potential threat.

China has steadily tightened control over information and computer security over the past two decades.

Banks and other entities that are deemed sensitive are required to use only Chinese-made security products wherever possible. Foreign vendors that sell routers and some other network products in China are required to disclose to regulators how any encryption features work.

BEIJING (AP)