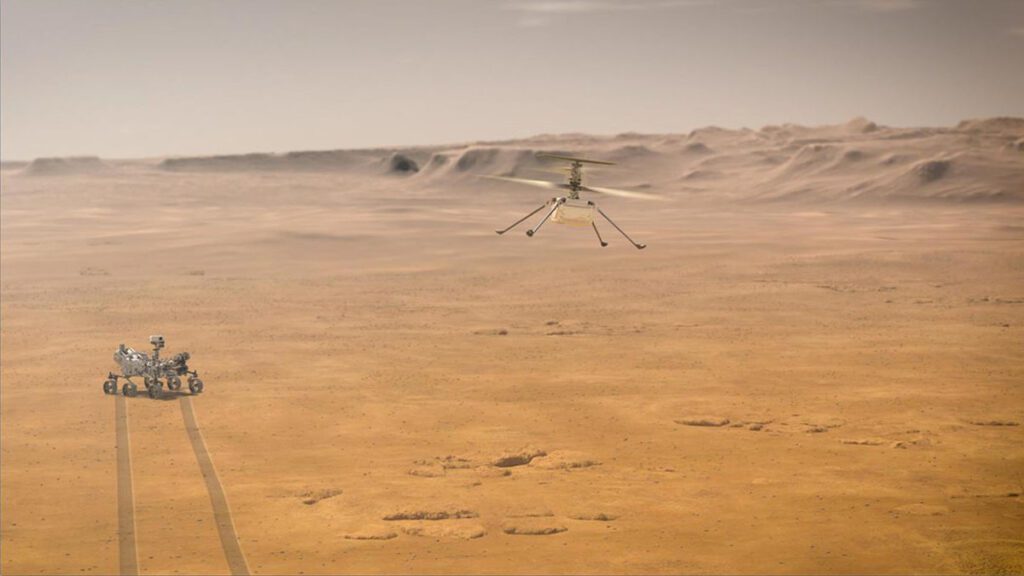

NASA is targeting no earlier than April 8 for the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter to make the first attempt at powered, controlled flight of an aircraft on another planet. Before the 4-pound (1.8-kilogram) rotorcraft can attempt its first flight, however, both it and its team must meet a series of daunting milestones.

Ingenuity remains attached to the belly of NASA’s Perseverance rover, which touched down on Mars Feb. 18. On March 21, the rover deployed the guitar case-shaped graphite composite debris shield that protected Ingenuity during landing.

The rover currently is in transit to the “airfield” where Ingenuity will attempt to fly. Once deployed, the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter will have 30 Martian days, or sols, (31 Earth days) to conduct its test flight campaign.

“When NASA’s Sojourner rover landed on Mars in 1997, it proved that roving the Red Planet was possible and completely redefined our approach to how we explore Mars. Similarly, we want to learn about the potential Ingenuity has for the future of science research,” said Lori Glaze, director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters.

“Aptly named, Ingenuity is a technology demonstration that aims to be the first powered flight on another world and, if successful, could further expand our horizons and broaden the scope of what is possible with Mars exploration,” Glaze added.

Flying in a controlled manner on Mars is far more difficult than flying on Earth.

The Red Planet has significant gravity (about one-third that of Earth’s) but its atmosphere is just 1 percent as dense as Earth’s at the surface.

During Martian daytime, the planet’s surface receives only about half the amount of solar energy that reaches Earth during its daytime, and nighttime temperatures can drop as low as minus 130 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 90 degrees Celsius), which can freeze and crack unprotected electrical components.

To fit within the available accommodations provided by the Perseverance rover, the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter must be small. To fly in the Mars environment, it must be lightweight. To survive the frigid Martian nights, it must have enough energy to power internal heaters.

The system – from the performance of its rotors in rarified air to its solar panels, electrical heaters, and other components – has been tested and retested in the vacuum chambers and test labs of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

“Every step we have taken since this journey began six years ago has been uncharted territory in the history of aircraft,” said Bob Balaram, Mars Helicopter chief engineer at JPL. “And while getting deployed to the surface will be a big challenge, surviving that first night on Mars alone, without the rover protecting it and keeping it powered, will be an even bigger one.”

The First Flight Test on Mars

Once the team is ready to attempt the first flight, Perseverance will receive and relay to Ingenuity the final flight instructions from JPL mission controllers.

Several factors will determine the precise time for the flight, including modeling of local wind patterns plus measurements taken by the Mars Environmental Dynamics Analyzer (MEDA) aboard Perseverance.

The Ingenuity Mars Helicopter will run its rotors to 2,537 rpm and, if all final self-checks look good, lift off. After climbing at a rate of about 3 feet per second (1 meter per second), the helicopter will hover at 10 feet (3 meters) above the surface for up to 30 seconds.

Then, the Mars Helicopter will descend and touch back down on the Martian surface.

Several hours after the first flight has occurred, Perseverance will downlink Ingenuity’s first set of engineering data and, possibly, images and video from the rover’s Navigation Cameras and Mastcam-Z. From the data downlinked that first evening after the flight, the Mars Helicopter team expect to be able to determine if their first attempt to fly at Mars was a success.

“Ingenuity is an experimental engineering flight test – we want to see if we can fly at Mars,” said MiMi Aung, project manager for Ingenuity Mars Helicopter at JPL. “There are no science instruments onboard and no goals to obtain scientific information. We are confident that all the engineering data we want to obtain both on the surface of Mars and aloft can be done within this 30-sol window,” Aung added.

On the following sol, all the remaining engineering data collected during the flight, as well as some low-resolution black-and-white imagery from the helicopter’s own Navigation Camera, could be downlinked to JPL.

The third sol of this phase, the two images taken by the helicopter’s high-resolution color camera should arrive. The Ingenuity Mars Helicopter team will use all information available to determine when and how to move forward with their next test.

“Mars is hard,” said Aung. “Our plan is to work whatever the Red Planet throws at us the very same way we handled every challenge we’ve faced over the past six years – together, with tenacity and a lot of hard work, and a little Ingenuity.”