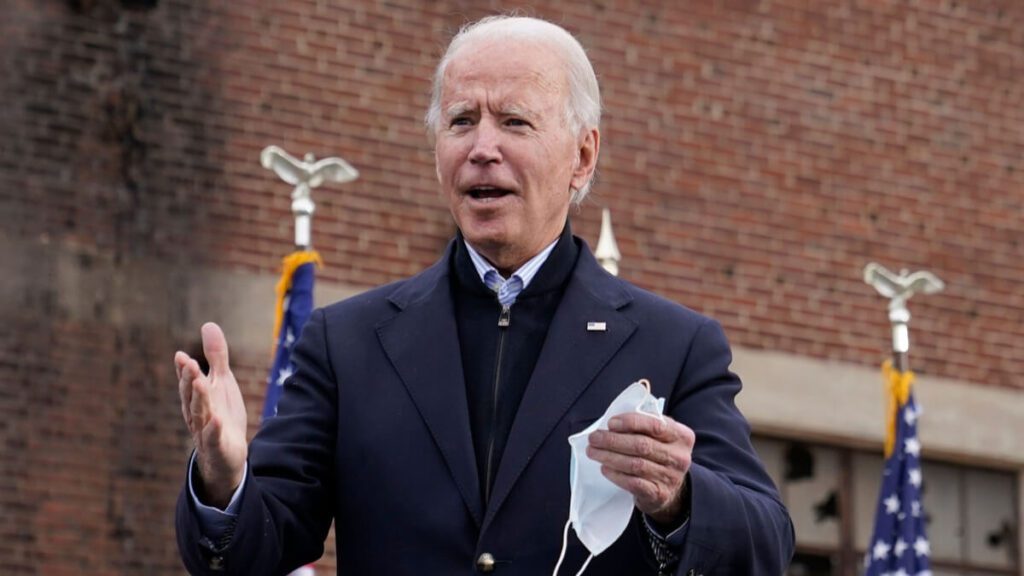

The White House began highlighting the $1.9 trillion COVID relief bill immediately after it gained final congressional approval on Wednesday, wasting no time in selling the public on President Joe Biden’s first legislative victory.

The West Wing began an ambitious campaign to showcase the bill’s contents while looking to build momentum for the next, perhaps thornier, parts of the president’s sweeping agenda. Biden will sign the bill into law on Friday, but the White House didn’t wait, turning the bill signing into a three-day event.

The president tweeted moments after the House of Representatives passed the bill that “Help is here — and brighter days lie ahead.” He later told reporters that “This bill represents a historic victory for the American people,” while the White House also released a slickly produced video touting the passage, and Democrats on Capitol Hill staged an elaborate signing ceremony.

Biden will make the first prime-time address of his presidency on Thursday to mark the one-year anniversary of the COVID-19 lockdowns and will use the moment to pitch toward the future and how prospects will be improved by the nearly $2 trillion aid package.

Animating the public relations outreach is a determination to avoid repeating the mistakes from more than a decade earlier, when President Barack Obama’s administration did not fully educate the public about the benefits of its own economic recovery plan.

“Barack was so modest, he didn’t want to take, as he said, a ‘victory lap,’” Biden, who was Obama’s vice president, said last week. “I kept saying, ‘Tell people what we did.’ He said, ‘We don’t have time. I’m not going to take a victory lap.’ And we paid a price for it, ironically, for that humility.”

As the White House works to get out its message, expect an uptick in travel by the president, first lady Jill Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris and her husband, Doug Emhoff, as well as Cabinet secretaries and others, according to a memo by deputy chief of staff Jen O’Malley Dillon. The document was circulated among West Wing senior staff members on Wednesday and was obtained by The Associated Press.

“He will be hitting the road, the vice president will be hitting the road, the first lady will be hitting the road,” said White House press secretary Jen Psaki, adding that the administration would also make officials available for local news interviews and other virtual events from Washington.

A blitz of interviews and events with more than 400 mayors and governors, including Republicans, will begin in earnest next week; the local officials will discuss what the plan means for their communities. There also will be an effort to plainly spell out the benefits of the plan and how it could affect each American.

O’Malley Dillon wrote that overall pitch is that the country “can be confident in knowing that the help they need will be there for them: to make it through financial difficulties, to get vaccinated so they can see their loved ones again, and to safely send their kids back to school and get back to work themselves.”

There will also be an effort to produce a steady stream of vaccination headlines, with the nation’s economic recovery intrinsically linked to inoculating Americans and getting them back to work.

Biden on Wednesday announced that his administration is aiming to secure an additional 100 million doses of the single-shot vaccine developed by Johnson & Johnson. He appeared at an event with executives from Johnson & Johnson and Merck, rival companies both producing doses of the new vaccine.

Many of those working in Biden’s West Wing are veterans of the Obama administration and they acknowledge that not enough was done to sell the 2009 recovery act — to the public or to Congress, with whom the White House had a shaky relationship — and highlight how it helped stabilize a battered economy during the Great Recession.

“I was here during that period of time,” said Psaki, “and I would say that any of my colleagues at the time would say that we didn’t do enough to explain to the American people what the benefits were of the rescue plan, and we didn’t do enough to do it in terms that people would be talking about at their dinner tables.”

The Obama bill faced headwinds because it followed the bailout of the banks, engineered under President George W. Bush, and came as the economy remained stagnant. This time, economic forecasts project a robust recovery by year’s end, and Biden should be able to point to concrete job growth.

The administration is not shying away from the enormity of the bill, which some in the West Wing have jokingly called a “BFD,” an echo of Biden’s famed off-color description of the Obama-era health care law. Harris, appearing at an afternoon event to promote the plan, called it simply “a big deal.”

The virus aid package is one of the largest enhancements to the social safety net in decades. Besides aiming to stop the pandemic and jump-starting hiring, money in the bill is supposed to start fixing income inequality, halve child poverty, feed the hungry, save pensions, sustain public transit, let schools reopen with confidence and help repair state and local government finances.

The White House has repeatedly pointed to polling that suggests that the relief bill enjoys broad support among Democratic and Republican voters, even though not one GOP lawmaker signed on to support it. Biden wooed GOP senators to no avail, but some Republicans feel the White House’s lack of compromise could hurt the administration down the road.

“I just really think they made a mistake. It takes serious work to make COVID relief a partisan exercise,” said Josh Holmes, a former aide to Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky.

Republicans, who have largely turned their attention to culture war issues, believe there will be opportunities to better push back when the White House moves on to more polarizing issues such as immigration, voting rights legislation and a potentially massive infrastructure and jobs bill that could also include climate change measures.

In Obama’s first term, it was the rollout of the Affordable Care Act, which came after the economic rescue package, that truly galvanized Republican opposition. The Obama White House secured its passage, but then the Democratic Party took a big hit in the midterm elections.

President Donald Trump ran away from his signature first-year accomplishment, the 2017 tax cut, which was unpopular and nearly unmentioned before Republicans took losses in the following year’s midterms.

The Biden White House believes that a Republican Party consumed with culture wars and in-fighting may not be able to organize opposition to other measures that poll well with the public, and it plans to stay on the offensive.

“You’ve got to create an echo chamber and amplify it,” said Adrienne Elrod, a Democratic strategist close to the White House. “We know that this administration for the next two years is going to pass a lot of legislation they need to pass, even without Republicans. They need to portray the Republicans as being on the wrong side of things people want.”

WASHINGTON (AP) — By JONATHAN LEMIRE